Table Of Content

SCEDs can be referred to as ‘personalized (N-of-1) trials’ when used this way, but they also have broad applicability to a range of scientific questions. Results from SCEDs can be aggregated using meta-analytic techniques to establish generalizable methods and treatment guidelines (Shadish, 2014; Vannest et al., 2018). Figure 1 presents the main family of SCEDs, and shows how personalized (N-of-1) trials fit into these designs (Vohra et al., 2016). The figure also distinguishes between experimental and nonexperimental single-case designs. In the current article, we provide an overview of SCEDs and thus a context for the articles in this special issue focused on personalized (N-of-1) trials.

Multiple-Baseline Design Across Settings

This type of design may be relevant for drugs that have rapid effects with a short half-life and behavioral interventions that have rapid effects (Coyle & Robertson, 1998)—for example, the effects of biofeedback on heart rate (Weems, 1998). Another design is the changing criterion design, in which experimental control is demonstrated when the outcome meets certain preselected criteria that can be systematically increased or decreased over time (Hartmann & Hall, 1976). The design is especially useful when learning a new skill or when outcomes change slowly over time (Singh & Leung, 1988)—for example, gradually increasing the range of foods chosen in a previously highly selective eater (Russo et al., 2019).

The Family of Single-Case Experimental Designs

(Note that averaging across participants is less common.) Another approach is to compute the percentage of nonoverlapping data (PND) for each participant (Scruggs & Mastropieri, 2001)[4]. There may be a period of adjustment to the treatment during which the behaviour of interest becomes more variable and begins to increase or decrease. In a multiple-treatment reversal design, a baseline phase is followed by separate phases in which different treatments are introduced. In a multiple-treatment reversal design, a baseline phase is followed by separate phases in which different treatments are introduced.

Terahertz chiral subwavelength cavities breaking time-reversal symmetry via ultrastrong light-matter interaction

However, that's not to say that the upper floor of an inverted floor plan can't have a bedroom -- in fact, many do. By keeping at least one bedroom on the same floor as the living area, a flipped floor plan makes a lot of sense from a multigenerational household perspective, as it gives the various members of the household both privacy and easy access to the living area. In a traditional multistory home, the kitchen and living area are on the first floor, and the bedrooms are upstairs. An inverted floor plan swaps the floors, putting the bedrooms on the first floor and the living area on the second or highest floor. The uniform failure of drug trials in Alzheimer’s influenced Bredesen’s desire to better understand the fundamental nature of the disease.

Charge-reversal nanoemulsions: A systematic investigation of phosphorylated PEG-based surfactants - ScienceDirect.com

Charge-reversal nanoemulsions: A systematic investigation of phosphorylated PEG-based surfactants.

Posted: Sat, 05 Feb 2022 08:00:00 GMT [source]

Or one treatment could be implemented in the morning and another in the afternoon. The alternating treatments design can be a quick and effective way of comparing treatments, but only when the treatments are fast acting. Single-subject research, by contrast, relies heavily on a very different approach called visual inspection.

During the baseline phase, they observed the students for 10-minute periods each day during lunch recess and counted the number of aggressive behaviours they exhibited toward their peers. They found that the number of aggressive behaviours exhibited by each student dropped shortly after the program was implemented at his or her school. In one version of the design, a baseline is established for each of several participants, and the treatment is then introduced for each one. The key to this design is that the treatment is introduced at a different time for each participant. The idea is that if the dependent variable changes when the treatment is introduced for one participant, it might be a coincidence. But if the dependent variable changes when the treatment is introduced for multiple participants—especially when the treatment is introduced at different times for the different participants—then it is extremely unlikely to be a coincidence.

Multiple baseline

The greater the percentage of non-overlapping data, the stronger the treatment effect. The most basic single-subject research design is the reversal design, also called the ABA design. The mean and standard deviation of each participant’s responses under each condition are computed and compared, and inferential statistical tests such as the t test or analysis of variance are applied (Fisch, 2001)[3]. (Note that averaging across participants is less common.) Another approach is to compute the percentage of non-overlapping data (PND) for each participant (Scruggs & Mastropieri, 2001)[4].

Expanded Treatment

When steady state responding is reached, phase B begins as the researcher introduces the treatment. There may be a period of adjustment to the treatment during which the behavior of interest becomes more variable and begins to increase or decrease. Again, the researcher waits until that dependent variable reaches a steady state so that it is clear whether and how much it has changed. Finally, the researcher removes the treatment and again waits until the dependent variable reaches a steady state. This basic reversal design can also be extended with the reintroduction of the treatment (ABAB), another return to baseline (ABABA), and so on. There are close relatives of the basic reversal design that allow for the evaluation of more than one treatment.

General Features of Single-Subject Designs

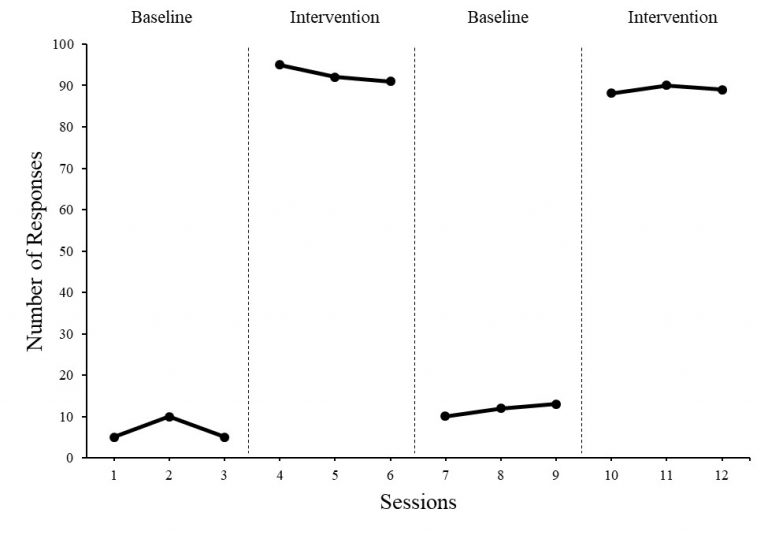

Perhaps something else happened at about the same time as the treatment—for example, the student’s parents might have started rewarding him for good grades. One solution to these problems is to use a multiple-baseline design, which is represented in Figure 10.3. There are three different types of multiple-baseline designs which we will now consider. In the top panel of Figure 10.5, there are fairly obvious changes in the level and trend of the dependent variable from condition to condition.

It can be especially telling when a trend changes directions—for example, when an unwanted behavior is increasing during baseline but then begins to decrease with the introduction of the treatment. A third factor is latencyOne factor that is considered in the visual inspection of single-subject data. The time between the change in conditions and the change in the dependent variable., which is the time it takes for the dependent variable to begin changing after a change in conditions. In general, if a change in the dependent variable begins shortly after a change in conditions, this suggests that the treatment was responsible.

The most common approach to evaluating the effectiveness of interventions on outcomes is using randomized controlled trials (RCTs). People do not all change at the same rate or in the same way, however; variability in both how people change and the effect of the intervention is inevitable (Fisher et al., 2018; Normand, 2016; Roustit et al., 2018). These sources of variability are conflated in a typical RCT, leading to heterogeneity of treatment effects (HTE).

No comments:

Post a Comment